Wendy M. Laybourn

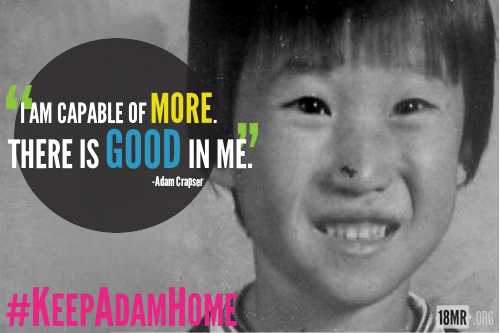

In early 2015, Immigration and Customs Enforcement served Adam Crapser, a 40-year-old Korean adoptee, deportation paperwork. Though adopted to the U.S. from Korea as a toddler, his adoptive parents never took the necessary steps to naturalize him. When Adam reapplied for a green card, the standard background check was flagged as he had previously served time for a crime he committed. Historically, international adoptees have not been thought of as immigrants, but, rather, as one of the family. Crapser’s case challenged these notions, leading many adoptees to rethink their own status.

In early 2015, Immigration and Customs Enforcement served Adam Crapser, a 40-year-old Korean adoptee, deportation paperwork. Though adopted to the U.S. from Korea as a toddler, his adoptive parents never took the necessary steps to naturalize him. When Adam reapplied for a green card, the standard background check was flagged as he had previously served time for a crime he committed. Historically, international adoptees have not been thought of as immigrants, but, rather, as one of the family. Crapser’s case challenged these notions, leading many adoptees to rethink their own status.

Crapser’s case represents the more than 35,000 other international adoptees without citizenship. Currently, children internationally adopted to American families automatically receive U.S. citizenship, but this was not always the case. Prior to the Child Citizenship Act of 2000, it was incumbent upon adoptive parents to know that they needed to naturalize their internationally adopted children and then take the steps to do so. Without a formalized system notifying parents of this, many adoptive parents did not secure citizenship for their children – some out of ignorance, others from benign neglect, and still others purposefully.

Of the estimated 35,000 international adoptees without citizenship, the majority are from Korea, due to the history of Korean adoption. Adoption from Korea began in the early 1950s, as a result of the Korean War, laying the foundation for the international adoption industry we see today. Prior to adoption from Korea, adoptions followed strict “matching” procedures whereby prospective parents and adoptive children were matched by physical features, temperament, and even religion. Korea ushered in a new approach to adoptive family making.

To date, over 150,000 Korean children have been adopted to the U.S., primarily to white families, making these adoptions transracial. Korean adoptees comprise 25% of all international adoptions to the U.S. and are the largest group of transracial adoptees now in adulthood.

As a result of Adam Crapser’s case, over the past three years Korean adoptees and their allies have been advocating for adoptee citizenship rights. A central part of their advocacy is political support for the Adoptee Citizenship Act, a piece of legislation that would retroactively grant U.S. citizenship to international adoptees not covered under the Child Citizenship Act of 2000.

In advocating for adoptee citizenship rights, Korean adoptees call upon their collective identity as adoptees to propel people to join the movement for “citizenship for all adoptees.” At a Korean adoptee social gathering in fall of 2015, Jen*, a 44-year-old Korean adoptee woman, declared, “It is our duty to support it [the Adoptee Citizenship Act] and call our senator, congressmen to get this bill pushed through. This could be any of us.”

Jen emphasizes her audience’s shared transnational adoptive status to engage people to identify with and act on behalf of vulnerable transnational adoptees. Although Korean adoption is not new, the shared status as Korean adoptee immigrants is. Jen’s words highlight for her audience their shared adoption history and shared responsibility to advocate for themselves and one another.

I spoke with 37 Korean adoptees, whose ages ranged from 21-56, to find out how Adam Crapser’s case had impacted how they thought about their citizenship and belonging and if they were involved in citizenship rights advocacy. Reflecting on why she got involved with adoptee citizenship rights advocacy, Alex*, a 30-year-old Korean adoptee woman, shared: “I’m feeling like it’s part of my duty to help these other adoptees that, through no fault of their own, don’t have citizenship. So, that’s one thing that I’m trying to do to actively accept [who I am as an adoptee].” Advocacy, then, becomes a pathway towards adoptees’ self-realization of their adoptee and immigrant identity. Prior to Crapser’s case, many adoptees did not consider their immigrant status as part of their identity.

Whether they had previously thought of themselves as immigrants or not, the threat of deportation demonstrates international adoptees’ enduring immigrant status. As with other immigrant communities, through adoptees we see again that immigrant status trumps family relations. As Kendra*, a 32-year-old Korean adoptee woman, stated: “[Who I am as an adoptee is] more important now than before, especially in the political environment…The whole anti-immigrant fever that's going on. It's [led me to] advocating for those people who are trying to go through the system and have lost or can’t. There’s not this easy process. I think using [my] personal experience to help people have a different perspective on other people’s lives and stories is really, really important and how I use being an adoptee.”

News of adoptee deportations sent shock waves through adoptee communities. The idea that adoptees could be deported from their families, country, and culture led many adoptees to reconsider their sense of belonging within the U.S. and who they are as immigrants. Their identity exploration and concurrent involvement in adoptee citizenship rights advocacy not only challenges long-standing narratives that minimize international adoptees’ difference from their adoptive parents but it also demonstrates how identity change happens and the process of collective action organizing.

To learn more about the history of Korean adoption, the common racial and ethnic identity issues Korean adoptees face, and the global Korean adoptee community, see:

Kim, Eleana. 2010. Adopted Territory: Transnational Korean Adoptees And The Politics Of Belonging. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Oh, Arissa H. 2015. To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Tuan, Mia and Jiannbin Lee Shiao. 2012. Choosing Ethnicity, Negotiating Race: Korean Adoptees In America. NY, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Also, watch akaSeoul, NBC Asian America’s seven-part docu-series featuring five Korean adoptees who return to Seoul for a Korean adoptee gathering. akaSeoul. 2016. NBC.

*Name has been changed

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Wendy M. Laybourn received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Maryland (’18) and is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Memphis. Dr. Laybourn’s research examines racial and ethnic identity formation, racialization, and racial meaning making. Her book, Diversity in Black Greek Letter Organizations: Breaking the Line (Routledge), was published this spring.

Wendy M. Laybourn received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Maryland (’18) and is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Memphis. Dr. Laybourn’s research examines racial and ethnic identity formation, racialization, and racial meaning making. Her book, Diversity in Black Greek Letter Organizations: Breaking the Line (Routledge), was published this spring.

Website: wendymlaybourn.com

Twitter: @wendymarieonly