By Jordan Slavik

Did you get the message that “You Have Died of Dysentery” on The Oregon Trail or discover that “The Cake Is A Lie” in Portal? Video games have become a leading form of mass media, now tripling the value of the film industry. [1] The popularity of competitive eSports for both viewers and corporate sponsors has likewise worked to entrench video games as important cultural icons. Given this increased influence and a new generation of university instructors who grew up with popular video games in the late 80s and 90s, it is not surprising that many scholars have recently pointed to the pedagogical utility of video games in the classroom. [2]

Historians especially have been concerned with how these games might help students better understand and explore the historical past. [3] This past summer, while teaching a course on the reception of history through video games, I was admittedly surprised with how useful certain games could become to students of history, when taught effectively.

Historians especially have been concerned with how these games might help students better understand and explore the historical past. [3] This past summer, while teaching a course on the reception of history through video games, I was admittedly surprised with how useful certain games could become to students of history, when taught effectively.

As historians have argued, the merits of video games in the university classroom do not stem from a shallow recreation of historical accuracy, but rather from an authentic recreation of historical experience. [4] Thus, with proper guidance, players of Sid Meier's Civilization IV or Age of Empires II can “experience” the ecological and geographical impacts on the maintenance of empire, the complex systems which make up these states, and the effects of technological and cultural disparities. [5] Such simulations allow students to understand the fears and concerns that necessarily accompanied most historical decision-making. When their cities are suddenly captured and destroyed without warning or retaliation, players of Rome: Total War, for example, can perhaps move a little closer to the ancient experience than they might through traditional scholarship.

Video games can bring a better understanding of the craft of historiography into the history classroom. Historians rely on factual evidence from the past, but the ways in which historians choose to order, prioritize, and assemble these facts remain their own. This “construction” of history is in many ways paralleled by a similar narrative within video games that is shaped by players’ decisions. This results in a historiographical experience influenced by the historical scope of the game as well as the amount of agency a player has in determining the storyline.

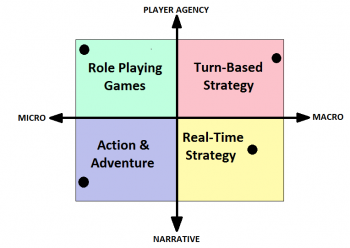

Player agency, in turn, varies across video game genres. The notion of gaming genres has been underemphasized and even incorrectly labeled by previous historians. Highlighting four different genres can offer some insight into how genre impacts the way games might be most effectively used in the classroom. In Role Playing Games, a player controls a single character with whom they complete quests, defeat enemies, and overcome challenges to gain experience and grow stronger. The skills, quests, and general direction that the game takes is largely up to the player. Action-Adventure games likewise see a player lead a single character through the game’s linear storyline. Turn-Based Strategy Games typically entail players controlling an entire civilization against its neighbors (either another player or an NPC); each player manages the military, economic, political, and religious elements of the civilization to achieve victory. This genre allows players to take their time making decisions and usually gives them a great deal of freedom in how they achieve their final goal of international supremacy. Lastly, Real-Time Strategy Games also emphasize players controlling an entire army or civilization, but, unlike in turn-based games, these games operate in real-time, forcing players to make quick decisions.

Player agency, in turn, varies across video game genres. The notion of gaming genres has been underemphasized and even incorrectly labeled by previous historians. Highlighting four different genres can offer some insight into how genre impacts the way games might be most effectively used in the classroom. In Role Playing Games, a player controls a single character with whom they complete quests, defeat enemies, and overcome challenges to gain experience and grow stronger. The skills, quests, and general direction that the game takes is largely up to the player. Action-Adventure games likewise see a player lead a single character through the game’s linear storyline. Turn-Based Strategy Games typically entail players controlling an entire civilization against its neighbors (either another player or an NPC); each player manages the military, economic, political, and religious elements of the civilization to achieve victory. This genre allows players to take their time making decisions and usually gives them a great deal of freedom in how they achieve their final goal of international supremacy. Lastly, Real-Time Strategy Games also emphasize players controlling an entire army or civilization, but, unlike in turn-based games, these games operate in real-time, forcing players to make quick decisions.

These genres fall into different quadrants in terms of the amount of player agency and the historical scope of the game. As such, each genre approaches simulating the historical past in its own way. Do these games focus on a single historical actor or on the complex systems behind great empires? Do they allow players to make their own decisions in exploring the historical past at the expense of the “factual” historical narrative or do they limit player choice in order to guide a linear storyline? In choosing one over the other, video games have both strengths and weaknesses as pedagogical tools through which to understand the past.

Considering the range of video game genres and the way agency works across those genres also reveals the limitations of historiography as a discipline. In choosing to focus on only one historical actor, proponents of “microhistory” like Carlo Ginzburg and Natalie Zemon Davis often lose sight of the forest through the trees. [6] Conversely, historical approaches that focus only on the “great men of history” are often likewise lacking. The importance of player agency also touches on one of the greatest weaknesses of modern historiography. Traditional histories are written and understood as linear narratives, leaving little room for contingency. As such, these histories often stray dangerously close to historical determinism, suggesting that the Confederacy was “destined” to lose at Gettysburg or that the Allies were always going to win the Second World War. While such linear narratives in both video games and traditional scholarship are perhaps necessary to present clear historical facts, they tend to underplay or even ignore the complexities and contingencies that embody real historical events and actors. Surprisingly, video games offer historians a way to present the past in a different light to show students that no historiographical model or method is without flaw.

[1] Entertainment Software Association (2017). 2017 Sales, Demographic, and Usage Data: Essential Facts about the Computer and Video Game Industry. Washington, DC: Entertainment Software Association.

[2] Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Squire, K. D. (2005). Changing the game: What happens when video games enter the classroom? Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 7(6).

Johnson, S. (2006). Everything bad is good for you: How popular culture is making us smarter. Hardondsworthy: Penguin.

[3] McMichael, A. (2007). PC games and the teaching of history. The History Teacher, 40(2), 203-218.

Wainwright, A. M. (2014). Teaching historical theory through video games. The History Teacher, 47(4), 579-612.

[4] Kapell, M. W., & Elliott, A. B. R. (Ed.). (2013). Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history. New York: Bloomsbury.

Kline, D. T. (Ed.). (2014). Digital gaming re-imagines the Middle Ages. New York: Routledge.

[5] Holdenried, J. D. (2013). Dominance and the Aztec Empire: Representations in Age of Empires II and Medieval II: Total War. In M. W. Kapell, & A. B. R. Elliott, (Eds.), Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history (pp. 107-120). New York: Bloomsbury.

Chapman, A. (2013). Affording history: Civilization and the ecological approach.In M. W. Kapell, & A. B. R. Elliott, (Eds.), Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history (pp. 61-73). New York: Bloomsbury.

[6] Ginzburg, C. (1976). The Cheese and the Worms. The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Davis, N.Z. (1983). The Return of Martin Guerre. Harvard University Press.

About the Author:

Jordan is a doctoral candidate and instructor in history at the University of Maryland with bachelor degrees in history and theology from Saint Louis University. His dissertation focuses on deception and decline in the ancient world through the writing of the Greek historian Polybius. Jordan's research interests also include interdisciplinary approaches to bridge STEM and the humanities in the classroom as well as understanding the historical past through video games.

Jordan is a doctoral candidate and instructor in history at the University of Maryland with bachelor degrees in history and theology from Saint Louis University. His dissertation focuses on deception and decline in the ancient world through the writing of the Greek historian Polybius. Jordan's research interests also include interdisciplinary approaches to bridge STEM and the humanities in the classroom as well as understanding the historical past through video games.