By Anna De Cheke Qualls

By Anna De Cheke Qualls

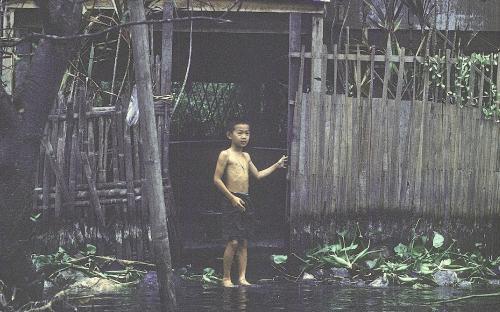

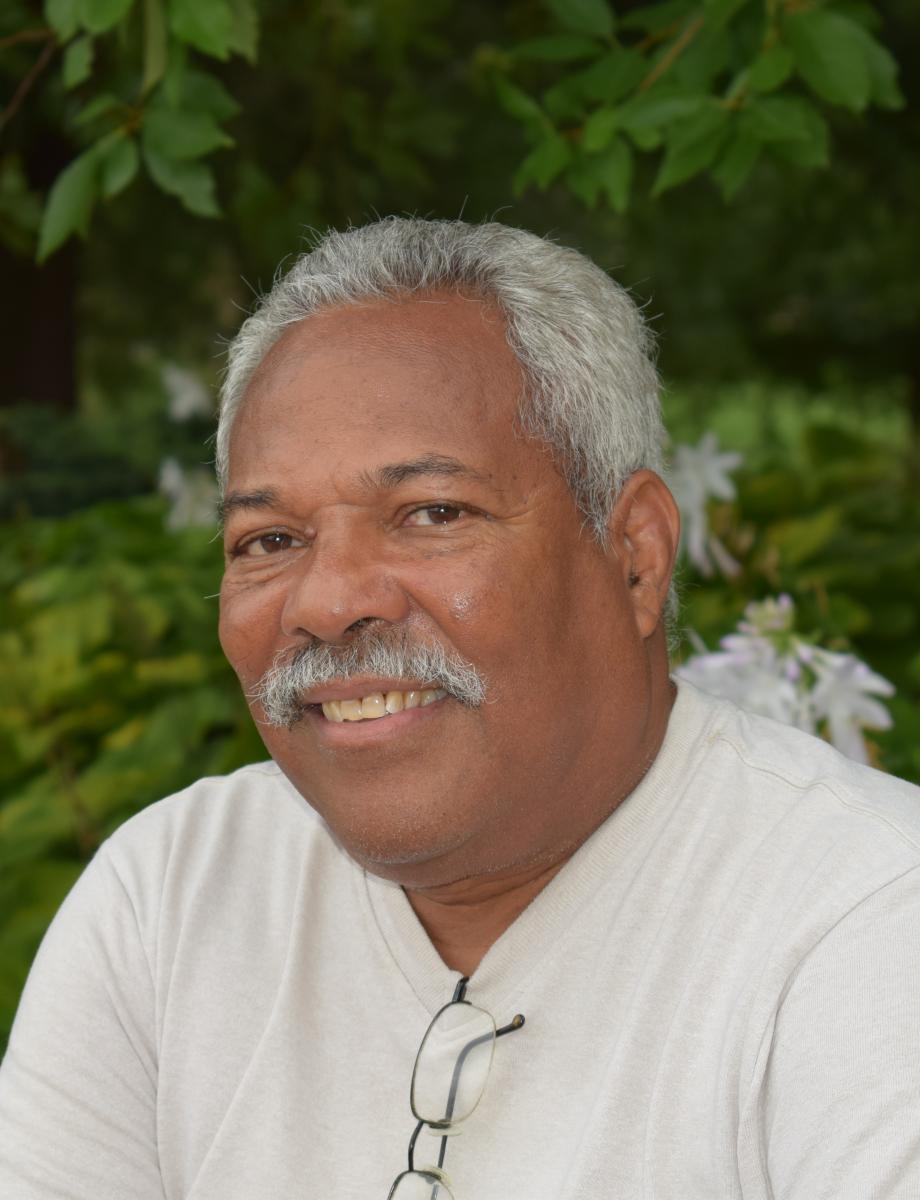

The year is 1980. Two young men are walking to Sribuangern, a remote village in the northwestern mountainous corner of Thailand. The surrounding green rice paddies are evidence of an agrarian, and as yet, moneyless economy. One of the men is Nick Arrindell (’83 PhD, Education), a doctoral student in international education and the other is his interpreter.

Arrindell is here to conduct doctoral field work. He aims to compare two non-formal rural development programs over a 9-month period. One of them is Sri Lanka’s Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, an organization founded in 1958, and the other is the Thai Ministry of Education’s Functional Literacy Program started in 1970--both successful models of host-country derivative programs, and both reach a segment of the population that has been and continues to be underserved.

Financed partially by a small grant and $6000-7000 of his own money, Arrindell navigates the international research process without much fanfare. He works with governmental agencies, village elders, and Buddhist monks to gain introductions. Over time, he identifies 57 participants who, at some point, successfully completed one of these literacy programs. He also interviews experts who were responsible for administering these education programs.

And throughout his stay, for both cultures, Arrindell remains a bit of a mystery. His physical stature and overall look is very similar to the participants of the study. He is often mistaken for a Malay Thai or in Sri Lanka, a Sinhalese. Arrindell attributes his success, in part, to his ability to blend in. “I learned how to gain acceptance in a different culture other than my own. I knew what it was like to be an outsider, and worked to gain the trust needed to complete the task ahead. And, most importantly, I learned how to gain cooperation at the village level without creating a level of threat. These prerequisite skills have remained with me as I moved forward as an international students and scholars professional,” recalls Arrindell.

Here’s the thing. This kind of field work is normative by today’s standards. But for that time and that space, it was highly unusual for a Black-American graduate student recruited for the ‘Other Race Fellowship’ by the University, to study international education. And beyond that, to conduct research overseas with the full support and encouragement of his dissertation committee. Anyone who is familiar with doctoral education can attest to the difficulty of forging such a path–-let alone in the late 1970’s.

Only a person with Arrindell’s audacity and background could pull this off. Someone with strong social and cultural capital. “My father was a merchant marine who traveled the world. My mother worked for IBM as a key punch operator, and came from a family of 14-–five men and nine women. All of the men and six of the women completed secondary high school, and some went further to complete a bachelor’s degree. Education was highly valued in my family, and was seen as the ultimate equalizer. My family believed in the American dream. In fact, I am not the first person in my family to have a Ph.D. One of my uncles became an assistant superintendent of schools in New York City,” remarks Arrindell. “Dr. Gladstone H. Atwell Middle School, named after him, was a reminder to me and our children that this remarkable honor came along with hard work, unwavering confidence, and an overall belief in the system.”

Arrindell, whose ancestry is Black-American and West Indian, grew up in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, and graduated from New York City’s public school system. He attended a small HBCU in Wilberforce, Ohio, called Central State University, where he studied sociology and history. It was his first time away from home, and first time in a predominately minority educative environment, but one that provided significant growth and development. “I knew few had this opportunity, so I had to finish, and do something for others,” remembers Arrindell. After graduation in 1969, Arrindell returned to New York to teach elementary and middle school. In 1976, he added a master’s degree in counseling to his resume. That year, he also applied to graduate school. After being waitlisted at other institutions, Maryland came calling with an offer of funding-–one Arrindell couldn’t refuse.

At the time, the University was under federal pressure to increase minority participation in graduate education. “Unfortunately, we walked into an institution that wasn’t ready for us.  I didn’t know about the political controversy until I got here. It was evident that they had not done their homework about the people they admitted--there was some resistance among the faculty and administration,” recalls Arrindell. “I can remember one early encounter where a faculty member said to me, ‘You speak English really well.’ To which I responded, ‘You’re not so bad yourself.’ And the person caught themselves, and said ‘Let’s start this again.’ And we restarted the conversation at a very different level.”

I didn’t know about the political controversy until I got here. It was evident that they had not done their homework about the people they admitted--there was some resistance among the faculty and administration,” recalls Arrindell. “I can remember one early encounter where a faculty member said to me, ‘You speak English really well.’ To which I responded, ‘You’re not so bad yourself.’ And the person caught themselves, and said ‘Let’s start this again.’ And we restarted the conversation at a very different level.”

“I tended to watch people carefully and called them out when something was odd. It was my way of protecting myself, and not getting steamrolled. The faculty and staff were not accustomed to seeing such an approach from a minority person, and I think that was part of my success. I made a point of tempering language but not hiding behind it,” adds Arrindell.

Initially on the educational administration track, Arrindell felt academically prepared, but not challenged to the extent he expected. He started taking courses in comparative and international education. He was fascinated and, perhaps, somehow also following in his father’s footsteps. “I often wondered if it was happenstance that I pursued this specific path. Still not certain, but I do know that being exposed early in my life to a very diverse cultural environment may have had something to do with it,” says Arrindell. For certain, he knows that it was his academic research, and reading that lead him to South East Asia.

Two years into the program, Arrindell married Pamela Parrish at Memorial Chapel. A flight attendant for Pan American Airlines, she played a critical role in the doctoral journey. She was not only the primary breadwinner during Arrindell’s studies, but his efforts became their joint project. The sacrifices, the negotiations, and complications were extensive. Arrindell was acutely aware that his Ph.D. had to be completed so that family life could fully realize the benefits of the doctoral struggle.

Between his role as a househusband, researcher, and father, Arrindell wrote his dissertation. “Staying focused was difficult and I just wanted to finish. I realized that writing itself is a process, and I needed to isolate myself to do it. Some of my most valued time was in my car--away from the house, the television, and others. Parking Lot 1 was one of my favorite spots. Other times, I would drive to a park, sit quietly, talk to myself, and read what I had written out loud. Or, I would get up in the middle of the night with an idea and write,” recalls Arrindell.

In 1983, Arrindell defended his doctorate. He got his first job eight months later at Fairleigh Dickinson University, as Director of International Student Affairs. “We advised about 23 different international clubs and organizations on campus. The International Student Organization had more influence on campus than any other student constituency. Nick had an incredible rapport with students, and is, to this day, in touch with some of them. He was warm, personable, open and engaging. He developed an informal network, which he tapped often, sometimes by just opening his office window. When he wanted to get the word out about something, he would say 'let's put it out on the drums,’” recalls former colleague Dr. Elizabeth Barnum, Director of International Student and Scholar Services, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Arrindell commuted to New York City by daily air shuttle out of Reagan National, even while he transferred to City College, CUNY, and Harlem. This was not by happenstance, but an intentional effort by the Arrindells to remain in Maryland. “It was difficult, but somehow we made it happen. As an educator, I always valued the educational process. I knew we had to give our children a strong foundation, and I hoped that one day they would understand that this was a part of our value system. We wanted our older child to have the greatest assets and access possible--and she had it,” remembers Arrindell.

As an administrator and former student, Arrindell knew only too well how to navigate the educational system, and what had to be done to propel not only his own children, but the international students as well. He continued to be this kind of an advocate for another 25 years as the Director of the Office of International Students and Scholars Services at The Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood Campus. Adds Arrindell, “I was keenly aware of how intellectual diversity as a construct was an attractive attribute brought to the American system of higher education. Institutions of higher education across the nation were the precursor of change. It was a huge paradigm shift. My generation of international educators was clearly in the forefront of this development.”

In more ways than one. When Arrindell’s activism started in the 1980’s, institutions weren’t talking about global citizenship or brain circulation. According to the Institute for International Education’s 2017 Open Doors Report, there were a combined 342,113 international undergraduate and graduate students studying in the United States in 1985. Thirty years later, that number was 974,926. According to NAFSA, in 2017 the figure climbed to 1,078,822. Institutions have recognized the incredible cultural, academic and economic benefits of supporting international exchange. “It’s been clearly acknowledged by most educators that an international vision has undoubtedly diversified our system, and has only strengthened the quality of our current educational system. It has provided an avenue for many of our domestic students to think about local, national, and world issues from a more dynamic and thoughtful perspective,” observes Arrindell. “And the international educator’s role is beyond just supporting international students and scholars. It’s a balancing act between internal and external forces that govern the enterprise. It is important to know how to welcome students and scholars, and to provide a safe space for them as they negotiate their new environment, and later embark on their career path,” he adds.

These days, we take for granted that universities have overseas campuses, and that students have greater global mobility. Internally, international students have more effective support systems, bridge programs, language instruction, and career advisement-–even as the international landscape and student/scholar needs continue to evolve.

These days, we take for granted that universities have overseas campuses, and that students have greater global mobility. Internally, international students have more effective support systems, bridge programs, language instruction, and career advisement-–even as the international landscape and student/scholar needs continue to evolve.

Arrindell championed these very programs and policies in a time when people of color were not represented in university leadership, let alone international education. Once again, his strong background and straightforward approach served Arrindell well. He made it a point to stay current in his field and gained the trust of the international student and scholar communities wherever he went. He was a leader in professional associations--NAFSA, AIEA and EAIE--for over 30 years. He built lasting relationships and found like-minded colleagues, such as Dr. Harvey Charles, Dean of International Education and Vice Provost for Global Strategy at the University at Albany, and Dr. Arlene Jackson, Vice President for Global Initiatives at American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU).

Arrindell and Charles worked together to help the leadership of the Association of International Education Administrators (AIEA) become aware of the need for greater diversity among its leadership ranks. “Not only was the leadership receptive to this idea, but we are both pleased that the board now adequately reflects the diversity found among senior international officers in the U.S. and to some extent around the world,” remembers Charles.

In 2013, Arrindell retired. The two-time Fulbright Scholar, leader in international education, father of two highly accomplished adults, and world traveler concludes, "My grandparents' birth certificate said 'colored', my parents' said 'negro', and I was considered 'negro', as well. Later, it was fashionable to be called Afro-American. This is where I came from-- ongoing external labeling and identity change. Now, I refer to myself as a Black-American. These very experiences informed my professional life, and I think this is why I was so effective in supporting international students and advocating for them on national and global level. At the same time, injecting much-needed diversity in higher education's leadership."

(Photo Credits: Dr. Nick Arrindell, Maynard Manzano, and Anna De Cheke Qualls)