There is a saying in Ecuador that says 'Quien a buen árbol se arrima Buena sombra lo cobija' - if you lean on a good tree you will be protected by a good shadow. For new graduate Viviana Cordero (’18 MA, Higher Education), a master’s degree is confirmation that familismo, the closeness of family ties, produces excellence.

Cordero was born in Santa Ana de los Cuatro Ríos de Cuenca, Ecuador. At more than 8200 feet, the metropolis of 700,000 rests in la sierra - the southern highlands of the Andes mountains. It is also home to the intersection of four rivers: the Tomebamba, Yanuncay, Tarqui, and Machangara, all of which merge into the Amazon. To honor this beautiful region, and the ancestors before her, Cordero is proud to call herself an Andina.

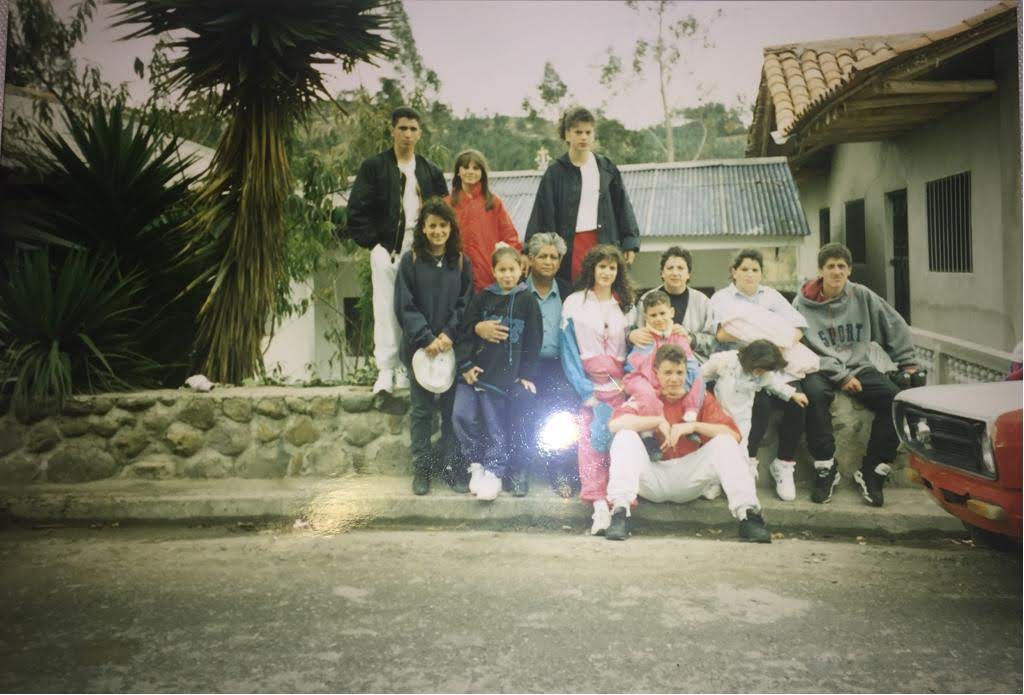

Throughout her childhood, Cordero benefited from having a large family, and the compadrazgo (co-parenting) from six aunts, and four uncles, and grandparents. Cordero credits her mother Ruth, however, for being the strong matriarch, and caregiver in her immediate family - which was expected of Ecuadorian women. When Cordero was just a toddler, the two of them immigrated to the Jackson Heights area of Queens, NY. Ruth, who did not finish 10th grade, came to this country for better opportunities to support her family in Ecuador - never imagining that as a former undocumented person at 16 years of age, she would return to the U.S. a few years later with a baby in her arms, through familial sponsorship.

“She was a single mother for a long time - it was her, and I mostly. She worked various jobs, and figured out a way to negotiate her schedule so that she could pick me up from school, and make la comidita (dinner). Although we were very financially limited, she made it work well. We always had food, a home, and, most importantly, each other. We often lived with aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents in a one-bedroom apartment. We shared spaces, beds, food, and resilience. Everyone worked hard. My sense of community comes from living and learning with family. And I really believe that was the foundation of my work ethic, and as a woman that's where I learned to take care of people, and be resourceful,” remembers Cordero.

Her stepfather, Wagner, has also been instrumental in her life. Like Cordero’s mother, he too came to the United States from Ecuador as a teenager, looking for a better life. “He is a doorman, and has always worked a lot. When my mother, and Wagner got together, he made it clear to me that he would not be taking my biological father’s place. Instead, he supported all of my educational goals in whichever way possible, and supported my mother as she made all important decisions related to me.  That meant a lot to me, even at a young age. While in high school, I remember how much I needed a laptop, as teachers were requiring us to type papers, and I often needed to stay after school for hours using the school’s computers to complete assignments. It was challenging. Seeing this, he saved up enough to gift me my first laptop. That meant I could finish homework at home instead of spending evenings at school. He has always looked for ways to support me, especially in my educational path,” remarks Cordero.

That meant a lot to me, even at a young age. While in high school, I remember how much I needed a laptop, as teachers were requiring us to type papers, and I often needed to stay after school for hours using the school’s computers to complete assignments. It was challenging. Seeing this, he saved up enough to gift me my first laptop. That meant I could finish homework at home instead of spending evenings at school. He has always looked for ways to support me, especially in my educational path,” remarks Cordero.

This idea of sharing and exchanging resources is an experience familiar to those who arrive in the United States as newcomers. For the Cordero family, financial uncertainty, and societal isolation were balanced by deep social capital, hope, and reciprocity. "The types of knowledge that students, particularly students of color, are bringing with them to college are unique. This knowledge base in many cases comes from the parents, and communities of Latinx students. Family is an important part of who these students are, and how they're coming into the higher education space. They're drawing on a rich community cultural wealth of knowledge, and support from their familial networks," says Dr. Sarah Rodriguez, Assistant Professor at Iowa State University's School of Education, who studies LatinX students' success in STEM.

Cordero reaped the benefits of her kinsfolk twice over – living in largely LatinX Jackson Heights, and spending many summers in Ecuador. She excelled in school, and saw education as a means to advance her family and community. When her mother remarried, Cordero became a role model for her two younger brothers Wagner and Damian – who eventually followed her path to higher education.

“There was no real abundance of money, things, but there was love, and hard work. When I finally made sense of what my mother had always said - 'tienes que ir a la universidad- la educación es algo no te pueden quitar' - I quickly figured out that I would have to work very, very hard to get a scholarship. Although I did not really understand tuition, and college costs, I knew for a fact that we could not afford to pay for college. So, I worked to keep my grades up, and I think it helped that my mother did not allow anything under a 100 at home. She motivated me to learn, learn, and learn some more,” remembers Cordero.

Resilience, hard work, and persistence paid off. Cordero was granted almost a full ride to Skidmore College through the Arthur O. Eve Higher Education Opportunity Program. It was a challenging experience for the first two years – culturally, socially, and academically. There were often moments when Cordero wanted to leave the institution. She was away from her network, and the academic self-actualization, and freedom she had come to know, was slipping away from her.

“Personally, the dominant cultural deficit narratives provoked the same kind of cognitive dissonance I experienced as a Latina child. I witnessed, and was the target of vile, demeaning atttitudes regarding the capacitity of Puerto Ricans while experiencing loving, positive, and encouraging, yet strict maternal support in the home throughout my K-12 education. I juggled these contradictions, and held on to my familial, and cultural assets throughout my undergraduate, and doctoral career. My career as a Latina educator, and administrator showed me that my experience was far from unique,” says Dr. Jennifer M. D. Matos of Mount Holyoke College whose recent publication reexamines the cultural deficit model, within Dr. Tara J. Yosso's cultural capital structure. (Matos, 2015)

In the fall semester of her junior year, Cordero went to Bolivia with the School for International Training. She spent the first two months in Cochabamba, and traveled to various cities before choosing to do a project in the lowland city of Santa Cruz. There Cordero co-filmed, and produced a documentary entitled Las venas abiertas de Santa Cruz: la calles hablan. It featured the work of ALALAY, a local NGO, which “was conceived with the mission to recover boys, girls and teenagers who have taken to the streets as their home, constructing opportunities, encouraging restitution, and exercising, and promoting their fundamental rights,” according to its mission statement.

This immersion fundamentally altered Cordero’s undergraduate experience. She regained her footing, and found herself once again in the driver’s seat of her own education. “That study abroad experience in one of the poorest Latin American countries set me up for a path, and life of service. I saw how education was changing lives, and systems, and I was eager to learn more about my communities of color. I returned to campus with a different perspective. I realized I had full control of my experience at Skidmore, and could take advantage of any, and all opportunities afforded to me. It was then that my interests in examining differences in gender, class, race, education, opportunity and access began to grow. The knowledge I gained through my, and my peers’ experiences motivated me to borrow strength from my community. I realized I, too, belonged, and deserved to be on campus, and this led me to successfully complete my degree,” remembers Cordero.

After graduation, Cordero followed her passion, and worked in various college access, and educational organizations. And eventually, she applied to the  University of Maryland’s master’s program in Higher Education, Student Affairs, International Education Policy (HESI). Once again, Cordero forged her own path, and made the most of this opportunity, as well. “If I wish to change the ways in which students of color, and their cultural capital are perceived in education, I have to be critical. I’ve been moved, and learned so much from my colleagues, and students in HESI, Belonging and Community at UMD, and UMD's Partners in Print, biological and chosen family, and especially my partner, Tobit Garcia. Their critical perspectives pushed me to recognize that I need to acknowledge that our society, and more specifically our educational system, is gendered, classed, and raced, and our knowledge of who has capital is constructed within historical and social contexts. Historically, people that share my social identities have been marginalized, and are underrepresented at many higher education institutions. Nonetheless, I acknowledge that my identities also hold privilege and power especially as I advance education levels. As I think about the work I have been doing at educational nonprofits, schools, and at UMD these past two years, I reflect on how my experiences, and those of my peers, have proven that institutions have not valued various forms of cultural capital that I and, many other students of color bring,” observes Cordero.

University of Maryland’s master’s program in Higher Education, Student Affairs, International Education Policy (HESI). Once again, Cordero forged her own path, and made the most of this opportunity, as well. “If I wish to change the ways in which students of color, and their cultural capital are perceived in education, I have to be critical. I’ve been moved, and learned so much from my colleagues, and students in HESI, Belonging and Community at UMD, and UMD's Partners in Print, biological and chosen family, and especially my partner, Tobit Garcia. Their critical perspectives pushed me to recognize that I need to acknowledge that our society, and more specifically our educational system, is gendered, classed, and raced, and our knowledge of who has capital is constructed within historical and social contexts. Historically, people that share my social identities have been marginalized, and are underrepresented at many higher education institutions. Nonetheless, I acknowledge that my identities also hold privilege and power especially as I advance education levels. As I think about the work I have been doing at educational nonprofits, schools, and at UMD these past two years, I reflect on how my experiences, and those of my peers, have proven that institutions have not valued various forms of cultural capital that I and, many other students of color bring,” observes Cordero.

And while Cordero continues to move forward in the higher educational space, she cannot forget where she came from and the sacrifices others have made on her behalf. “I would like to continue serving students, advocating for those who are underrepresented at our educational institutions, and celebrating cultures of people who have given their lives to open doors for me and mine. I wish to grow my appreciation and understanding of cross-cultural communication, leadership of students of color, and identity development. As a first-gen college student, a Latina, an immigrant, an English-language learner, I understand the importance of diversifying conversation in a classroom and empowering students. I wish to continue developing programs that support people of color through college, and beyond. In this way, I wish to promote equity in education,” concludes Cordero.

More information about Viviana Cordero can be found here.

(Photo Credits: Anna De Cheke Qualls, Viviana and Ruth Cordero)

Jennifer M. D. Matos (2015) La Familia: The Important Ingredient forLatina/o College Student Engagement and Persistence, Equity & Excellence in Education, 48:3,436-453, DOI: 10.1080/10665684.2015.1056761