It’s common practice for universities to empty out in the summer as researchers go out in the field. Dr. Jeremy Purcell, a research scientist at Maryland’s Neuroimaging Center, did something a little different. Through the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI), he traveled to India’s Doeguling Tibetan area to teach Tibetan monks and nuns something about neuroscience.

It’s common practice for universities to empty out in the summer as researchers go out in the field. Dr. Jeremy Purcell, a research scientist at Maryland’s Neuroimaging Center, did something a little different. Through the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI), he traveled to India’s Doeguling Tibetan area to teach Tibetan monks and nuns something about neuroscience.

With direct approval by his Holiness the Dalai Lama, the concept for ETSI evolved from a desire to pair science education with the existing multi-year training at major Tibetan monastic universities, such as Gaden, Sera, and Drepung - all located and exiled in southern India. From 2008 to 2013, a comprehensive and sustainable curriculum was developed for delivery between 2014 and 2019.

According to ETSI’s mission statement, “ETSI is designed to give Tibetan monastics new tools for understanding the world, while also providing them with fresh perspectives on how to employ and adapt time-tested, Buddhist, contemplative methodologies for the relief of suffering in the contemporary world. Additionally, scientists and science educators are encouraged to learn more about the Buddhist science of mind and what it can contribute to the understanding of human emotions, the nature of consciousness, and integrative approaches to health and well-being.”

Each of the last six summers, faculty from Emory University and other institutions presented Tibetan monks and nuns with intensive courses on biology, neuroscience, physics, and the philosophy of science. Through six hours of contact time each day for three weeks, students were exposed to experiential learning, discussions, lectures, demonstrations and a final exam. Distance learning was made available to other monasteries interested in the program. Additionally, a large repository of translated materials and textbooks were created to ensure sustainability.

Purcell, along with all of the ETSI program faculty taught their courses in English, and as a result, were paired with a Tibetan translator. While the Tibetan monastics came well versed in their own disciplines, such as Buddhist philosophy, debate and logic, they were eager to acquire new knowledge. Fortunately, Purcell’s experience with active learning teaching and cognitive neuroscience as Dr. Brenda Rapp’s postdoc at Johns Hopkins University positioned him well to engage the ETSI students. “As well, I had read some of the Dalai Lama’s books – such as How to See Yourself as You Really Are - and was interested in the Tibetan Buddhist way of thinking such as the idea of mindfulness. The program also made sense in terms of how I think about things – the importance of communicating science to a different culture, and faith really appealed to me. I also appreciated the dialogue that was a part of this experience,” says Purcell.

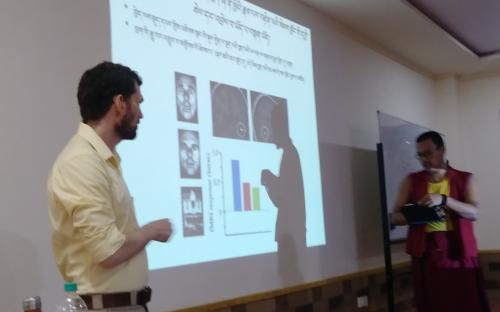

In the classroom, Purcell would deliver information to students, followed by the translator. There was on-going back and forth between the two presenters. “It was an interesting way to teach because there were a lot of pauses between what you said. Sometimes the translator would go on for much longer after I spoke because the translator would also explain concepts, and frame them in a way the students could understand,” says Purcell. “I found myself trying to tune into facial expressions to try and see if they were getting the material or not. And because their academic tradition is very different, we also covered some basic information,” he adds.

“My students were extremely talented, quick and highly educated. They were also very verbal. Every night, in front of the monastery hundreds of monks would debate each other on a variety of topics. In class, they would ask questions in this debate style – they would make a point, and I would have to make a counterpoint. It was interesting to engage in this logical dialogue,” remembers Purcell. “And now, they’re trying to integrate science into these very same debates, as an extension of their existing educational process,” he adds.

Unique to ETSI, Purcell was also faced with questions that don’t normally come up in a U.S. university setting. He was asked about his perspectives on enlightenment and the Buddhist practice of ascetic self-mummification. “I was asked ‘as a scientist, how do you perceive reincarnation or a predisposition to certain behaviors, such as an infant playing with a certain toy?’ That type of inquiry in a classroom was new. I offered an explanation as a scientist – and our focus on evidence. The fact that I could do that and feel really welcomed and appreciated, was extremely valuable,” observes Purcell. “I had to be very conscientious and send the message that we, as scientists, are not here to attack a faith but just working to understand the natural world. Even here in the States, I think these types of exchanges could be really helpful.”

For Purcell this program was an extension of his interest in university teaching, and active learning in the classroom. “Every afternoon, this is exactly what we did, we held flipped classroom sessions. We created activities that would engage the monks and nuns. But I think, what made this experience unique was the mixture of cultures and learning traditions, which also resonates with our undergraduate classrooms here in the States,” says Purcell. “As well, I think there is a lot to be said for creating conversations between faith-based folks and scientists, and for thinking about science more ethically,” he adds.

“ETSI program is a wonderful platform for the monks and nuns to acquire modern science knowledge and to have a glimpse of the educational system in the West. Not only that, they are able to experience and learn new strategies for teaching - imparting knowledge while they themselves are being taught by the ETSI educators. Due to these experiences, the students have increased their curiosity and over the course of time, as well as their interest in science,” remarks Tenzin Yangzom, a Biology and English faculty member at the Jangchub Choeling Nunnery, Mundgod, which participates in the ETSI program.

This summer, ETSI graduated its first cohort of 150 monastic students. At the same time, the program kicked into its Sustainability Phase (2020 – 2026), where the focus shifts toward deeper curriculum development, training on pedagogy and research, and the creation of additional teaching resources. Purcell hopes he is invited to play a part in these efforts.

As Purcell reflects on his unique summer experience, it appears he too was transformed. Purcell recalls a poignant interaction with one of the Buddhist nuns. After classes one evening, they were talking about contemporary music. “I asked her for her favorite song. She responded, ‘It’s Imagine by John Lennon.' I said, ‘You know one of the verses in the song talks about imagining the world without religion. Do you think that would good – having no Buddhism?’ She said, ‘We wouldn’t need Buddhism if the world was a better place.’ That interaction made an impression on me,” recalls Purcell. “For the monastics I met, Buddhism isn’t something everyone needs. That’s a very positive and healthy way of thinking in a sometimes difficult world. The idea that you wouldn’t need religion because the world is so good is very appealing,” he concludes.

More information about Dr. Jeremy Purcell can be found here.

(Photo credits: Jeremy Purcell; Header photo: Dr. Ken Paller, translator Tulku Lobsang Khennrab, and Jeremy Purcell)