By Anna De Cheke Qualls

Ashley Minner tells the story of the Lumbee in East Baltimore to anyone who will listen. It is a journey of members of the largest tribe east of the Mississippi through hardship, poverty, racism, identity and community.

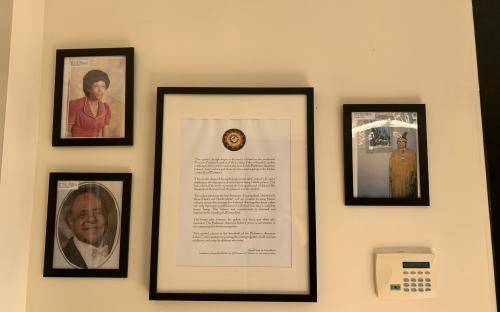

Her narrative always includes the Great Migration, following World War II, of Indians from tenant farms in North Carolina to an area in East Baltimore City between Washington Hill and Upper Fells Point. The Lumbee never lived on a reservation even in their native North Carolina, but they called their new Baltimore home ‘the reservation.’ The surge to Baltimore continued into the 1970s and brought thousands of Lumbee to the city. Today, the Baltimore American Indian Center (BAIC) and South Broadway Baptist Church are the surviving cornerstones of the original community that was formed.

“[The reservation] was a positive term because, at that point, Indian people could come here and they knew exactly what to look for. Baltimore Street was their ‘reservation.’ It was an intentional community, not an undesirable piece of land where people were made to stay. People were proud of what they established here,” says Minner.

She continues, “It is very different, geographically, than our tribal homeland, which is mostly farmland and swamp. It was a place, in those years, where you could go and see other people who looked like you, who understood who you were and where you came from. This was particularly important in a place like Baltimore, which, to this day, is understood to be mostly black and white. All of a sudden, there was this influx of Indians who didn’t look like the Indians on TV. People ask what we were. So the reservation was the place in the city you could be and not have to explain all that.”

Minner, who grew up in Dundalk, is a first-generation Lumbee of the Baltimore community. She’s also a doctoral student in American Studies. Her dissertation focuses on the changing relationship between the Baltimore Lumbee community and the neighborhood where they first settled. After many years as a visual artist, she decided to return to graduate school.

“I did not want to misrepresent us. I needed to go back and understand why our life experiences are such they are, and why are we seem to be following common paths. I did not see the recurring themes in our stories as being accidental - and writing an eventual book was something I wanted to do for my community,” says Minner.

Minner has a long history as a well-known voice for the Lumbee. She served on the executive board at BAIC for many years, ran the Title VII Office of Indian Education program in the Baltimore City Public Schools for nine years, has been an active member of Alternate ROOTS, was an officer on the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs (MCIA) through the Governor’s Office of Community Initiatives, a member of the Teachers Advisory Group Member at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and a speaker/storyteller at over 50 events.

E. Keith Colson, Director of Ethnic Commission for the State of Maryland Governor’s Office of Community Initiatives met Minner when she was a youth participant in the cultural program at the Baltimore American Indian Center, which he directed in the 1990s. He later worked with her as an adult, when she served as a representative for the Baltimore area of MCIA. “It was a governor appointed position and Ashley worked tirelessly for the betterment of American Indians in Maryland. She was passionate, motivated and caring,” he says.

Minner’s fellowships and awards include the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute’s Innovative Cultural Advocacy Fellowship, the Rockwood Leadership Institute Fellowship for Leaders in Arts and Culture, the Soros Foundation’s Open Society Institute Baltimore Community Fellowship, and twice the Roothbert Fund Fellowship. She has had ten national solo and 21 group exhibitions of her artwork – with the most recent at the University of Pennsylvania’s HUB-Robeson Galleries and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Center for the Study of the American South. She is also a multiple grant recipient of ROOTS and the Maryland State Art Council’s various programs. Minner is currently Professor of Practice at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Department of American Studies, and just won the American Folklore Society’s Polly Grimshaw Prize to continue archival research in collaboration with Baltimore Lumbee elders.

And while Minner may appear a confident Lumbee now, the journey to this wasn’t easy. Like many in her tribe, the struggle to understand identity has been a theme for centuries. Growing up in Dundalk, Minner often felt out of place.

Today’s Lumbees are a fusion of different tribes formed over 200 years – largely composed of the Cheraw, then a mix of Siouan, Algonquian, and Iroquoian speaking tribes. They also have European and African ancestry. Within the greater Native American communities in the U.S., the Lumbee have occasionally experienced exclusion. Even with the U.S. government’s partial recognition of the tribe in 1956, the Lumbee continued to experience racism, and inequality.

Especially with movement to manufacturing cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia and Detroit, Lumbee began to marry people of other races and ethnicities. And when they did, their tribal identity became even more complex.

“Here, they married or partnered up with all kinds of people. We have Polish Lumbees, Mexican Lumbees, like every kind of Lumbee. My dad is white, and my mom is Lumbee. My husband’s father is black, and his mom is Lumbee. Growing up, Thomas [my husband] and I sometimes felt out of place,” says Minner.

Today, Baltimore’s historic ‘reservation’ is known for its LatinX population. Areas of Southeast Baltimore County, like Dundalk, Rosedale, and Essex, now have significant Lumbee populations. As they were able, many Lumbee followed waves of flight out of Baltimore city to enter into private industry, work for Western Electric, Bethlehem Steel or General Motors. This was coupled with the city’s multiple attempts at ‘urban renewal’ and the forced relocation of its underserved residents.

“By the time I was born [in 1983], the ‘reservation’ was over. And we have watched this part of the city gentrify. I once thought I knew where to point my finger—as in who to blame—and I still want to point at the ‘yuppies’ who have now settled in, but the truth is that it’s a complex situation. Over the years, there have been various urban renewal plans that didn’t happen well or at all. When you are watching it happen, gentrification seems sudden. But as a community, we are suffering from planning decisions that were made decades ago. In the 1950s the Lumbee community had shops, more churches, even bars – now all gone. The city leveled a lot of it. For example, the former Moonlight Diner [Greek-owned, heavily Lumbee-patronized] up the street was one of the first places Indians arriving from the Jim Crow South could go to sit down inside and eat,” says Minner. Not a trace of it is left today.

Minner heard the stories of the Lumbees in Baltimore – from her mother, grandparents, aunt, and cousins. They introduced her to pow wows, and cultural events, and set an example through volunteer work within the community.

“I took her to the Lumbee church and to BAIC and exposed her to the native dress, food, and culture. Ashley grew up attached to her Indian roots, and developed a love for our community,” says Minner’s aunt, Jeanette Jones, an elder leader in Baltimore’s Lumbee community and retired director of the Indian Education Program of Baltimore City Public Schools.

And while Minner had her tribe, the outside world was often incompatible with her upbringing. The Lumbee just didn’t fit pop culture’s ideas about Indians.

“People thought I was Asian or Mexican. I knew I was Indian and I said I was Indian. But I was self-conscious for a number of reasons,” says Minner. “For one, I am light-skinned. If people constantly ask you if you are something else, you start to wonder. And there are always ignorant comments like - ‘you can’t be Indian because they don’t exist anymore,’ or ‘I am Indian too because everyone is part Cherokee,’ or ‘you can’t be Indian because you don’t ride on a horse and you don’t live in a tepee.’ By the time I was in high school I was making art about it.”

Eventually, Minner attended the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) for both her undergraduate and master’s degrees. To this day, much of her work pays homage to the Lumbee – and elevates the notion of identity and connection to place and people.

“When I was teaching art to young Indian children, I wanted them to know that their roots run deeper than what they might realize; that they’re part of another place and this place, and part of a legacy that’s so much greater than ourselves. They belong here, as much as they belong anywhere. They’re allowed to be here; they look how they look for a reason. They look exactly how they should look,” says Minner.

Her aunt also benefits from Minner’s participation in the Lumbee community.

“We just exposed Ashley to experiences, and she ran with it. Now she exposes me to native things, and helps me to revive [my own] memories I guess I displacedabout growing up as a Lumbee girl in our native community.”

As Minner continues to make art and complete her archival research with the tribe’s elders, she does wonder about the future of the Lumbee community in Baltimore.

“I don’t know what would happen to our community without the Indian Center and the church. There are real questions. We are pretty spread out, and five or six generations into intermarriage, in some cases. If people want to be involved, it is a conscious decision, and a lot of effort on their part. I never really called myself an activist. Other people have called me that. Now I realize that not everything is for me to do. I have a skillset and that’s my contribution – and I do what I do with truth, love and respect. That’s what I really care about now. I am only 36 but I spent most of my life in service, and really pushing myself. At this point, I would like to finish my dissertation, put something out there for my community, then go back to being an artist,” concludes Minner.

More information about Ashley Minner can be found here.

(Photo credit: Sean Scheidt and photos of BAIC by Anna De Cheke Qualls)