By Anna De Cheke Qualls

A birth certificate that says ‘colored’ is a ticket to a lifetime of challenges. No one knows this better than Dr. Maurice W. Dorsey (PhD ’83, Education Policy). In various leadership roles over his distinguished 42-year career, Dorsey spent his life working for the public good, while at the same time, making sure that his blackness, and sexual orientation did not overtly "threaten the status quo."

At 71 years of age, Dorsey tells a remarkable story. In 1947, Baltimore’s "Negro-only" Provident Hospital had a polio outbreak, and thus Dorsey was born at home. As the youngest of three siblings, he spent the first part of his life living in Edgewood, Maryland’s segregated, and substandard housing - administered by Edgewood Arsenal (now Aberdeen Proving Ground). The homes had pot belly stoves in the living room, a wood cooking stove in the kitchen, and an icebox.

“My mother kept the house immaculately clean, and it was as nice as it could possibly be in light of the fact that we were considered poor by American standards. As a child, I did not know the difference. We had good food, good clothing, and shelter,” recalls Dorsey. Eventually, the housing was integrated, and improved but still owned by the federal government for the benefit of military, and civilian families. Housing units included a gas range, a refrigerator, wall-mounted kitchen cabinets, ceramic tile bathroom floors, and walls. “There were Negro, White, Hispanic, and mixed race families all living together in the safety of a military environment. It was much better than the off-post housing for Negros. I saw cultural diversity very early in my life living in a relatively stable environment. Once you left military property, the segregation, and racism was highly prevalent,” he adds.

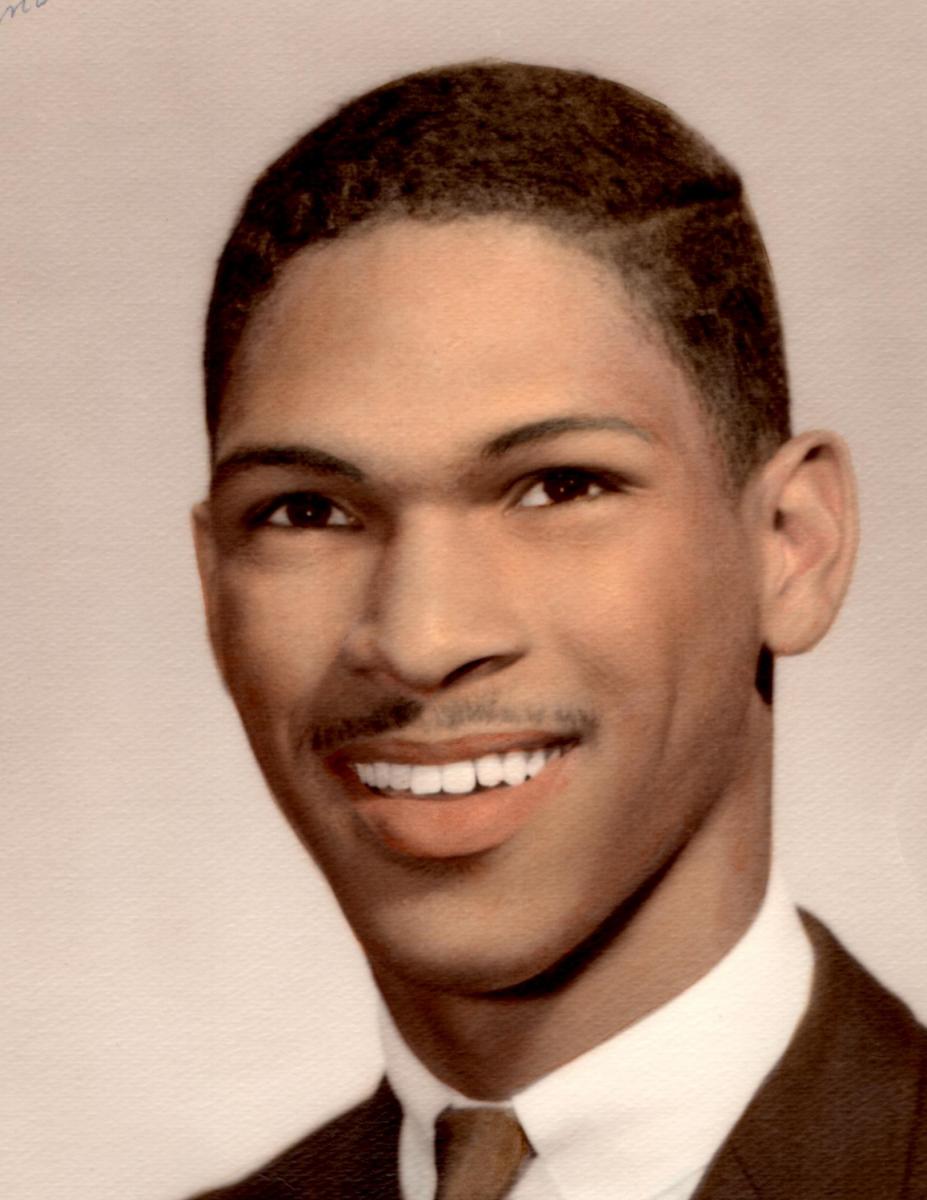

By 1960, Dorsey’s parents were able to afford building a three-bedroom rancher in Forest Hill’s segregated, and remote community. Despite living as any middle class family, US Route 1 separated the white, and black neighborhoods. Four years later, Dorsey entered 11th grade in Bel Air’s all-white Senior High School. “As a senior, I was the only black student in my class of 460. I got along well with everyone, and found integration acceptable for the most part. Still, for some I was not welcome – the school bus driver, some of the students, teachers, and the school administration. And I swallowed a lot of insults, and slights,” remembers Dorsey. “But I was durable, and strong. Living in Edgewood’s military housing was my social foundation for the all-white school. My mother, and my teacher the late Robert E. Lee Ross, coached me through without any racial clashes, even though I was often called a ‘nigger.’ I made history in a small way. I graduated in the spring of 1965, and was nominated the ‘friendliest senior of the year’ by my all-white classmates,” he adds.

That fall, Dorsey entered the University of Maryland. It was a tumultuous, and unwelcoming experience. Dorsey was moved from three dormitory rooms because majority students did not want to live with a black man. He lived in 341 Easton Hall, a single room, for four of his five undergraduate years. Academically, Dorsey struggled to keep his focus, changing majors three times. “My advisors were discouraging, and I was alone in every sense of the word, except for two influential mentors who cared enough to guide me to degree completion. They were the late Dean Marjorie Brooks [of the College of Home Economics], and Dr. Pedro Ribalta, a visiting professor from Spain,” he recalls. “You must consider at this time Blacks were not welcome on the College Park campus. In my generation, Negros were tracked to attend Maryland State College (now the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore). There were few who had my identity, and we were challenged to the max by the faculty, and the administration. I had an advisor in the Business School tell me to go to a junior college because I could not cut the mustard at Maryland,” he adds.

Dorsey graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Family and Consumer Sciences (then called Home Economics), followed by positions at Harford Community College, Baltimore City Public Schools, and Morgan State University. “Then, I was ashamed of Home Economics. What man wanted to be in Home Economics? And a gay man, majoring in Interior Design. I had everything I didn’t want around me, but I needed to get out of school and, get my GPA up,” recalls Dorsey.

In 1974, while working four part-time jobs, Dorsey concurrently enrolled in, and paid for a Master’s from Johns Hopkins University, and another from Loyola University of Maryland – finishing both within a year of each other. In 1976, he was recruited by the University of the District of Columbia (UDC) for a leadership role in its Cooperative Extension Service.

And this is when Dorsey got a call from the University of Maryland’s Assistant Dean of Graduate Studies, Archie L. Buffkins. For federal compliance purposes, the University’s Other Race Fellowship was established to recruit a cohort of underrepresented students for doctoral study. The award covered a significant portion of Dorsey's tuition, and about a $50 per month stipend. “Dr. Buffkins was a defining person in my life. And I told him, 'I would love to but I am tired.' The trajectory of my education had been difficult because I worked full-time. He didn’t push me but he did say ‘you will be making history at UDC, and the University of Maryland by having a Ph.D.’, and I realized this was an opportunity of a lifetime,” recalls Dorsey.

Once matriculated, Dorsey stayed mostly to himself throughout his graduate career. Despite having faculty members for academic support, the services available to graduate students today were wholly absent. “I was conditioned to know that I was Black, and unwelcome, and part of a political process leading to integration – in other words, a huge change in the United States. I did see the point of participating in this national political process, but I was alone. I was too black to be white, and too white to be black,” he says. “I would dress very expensively, despite being in debt. These clothes helped me camouflage my loneliness, and pain. I did not want to appear distressed, so most people thought I was ok. Anything I was feeling within was invisible to others.” Moreover, working full-time in D.C., and commuting from Catonsville (Maryland) each day, Dorsey was physically, and emotionally worn out, and had very little reserve left for social interaction.

“I kept this pace for five years, completing assignments at night, and on weekends. If there was any down time at work I used that, as well. I was on a mission to complete my Ph.D. In addition, I had elderly parents, a partner, and a mortgage. I survived because I was young at the time, and hungry for upward mobility. I had one friend at the University, Nick [Arrindell], and our lamentations, if any, were discussed in the hallways, by vending machines, or walking to parking lot A. Occasionally, we covered classes for each other. And I had no idea that a Graduate School even existed,” observes Dorsey.

Some of the other students in his fellowship created an informal support group. Dr. Nicholas Arrindell (PhD ‘83, International Education) was one of these students. “In a strange, and awkward way, we were like step children brought to the campus. We were the new entrants who walked into a graduate program with little or no support systems in place. The level of counseling/advisement for doctoral students was limited to none. We had faculty, and some staff, who were quite resistant to change. In retrospect, many of us did not know what to expect, and were equally naïve about the graduate process. I will concede it was a learning process for all concerned. Moreover, I never depended on the University for my social life. I was a true New Yorker, I went to class, punched in, and punched out. I was always prepared to challenge people but I did it in a way that was civil, and moved on. Over the years, the institution did try to make some overtures to create an easier transition for new doctoral students. The doctoral process is designed to select-out individuals. I felt the graduate programs were designed to instill intellectual rigor that prepared one to question, document, and produce new knowledge. The process was rough at times, full of uncertainty, and I felt that that we were being scrutinized on a constant basis. The faculty had the ability to determine whether you would ultimately deserve your hang-out card, the Ph.D. This is a snap shot of my experience as a full-time graduate student at Maryland,” remembers Arrindell, former Special Assistant to the Assistant Provost, and Director of the Office of International Scholars and Student Services at The Johns Hopkins University.

Dorsey did not gravitate toward the black student support group. “Because I came through the Civil Rights Movement, and we were fighting for equality, I would often sit alone, and if someone joined me that was fine, but I did not push for acceptance from whites or blacks. If I sat in segregated groups, I would not gain the benefit of a whole education. But I could understand why a number of minority students felt they needed each other to lean on.”

The late Dr. Daniel Huden, professor in the College of Education, guided Dorsey through the Ph.D. program. Huden was a steady influence throughout these five years, providing strong encouragement, regular communication, and support. Other faculty, according to Dorsey, weren’t as helpful. “Minority students weren’t important to faculty. Most focused on their publications for tenure. I think that in my case, I could have used a little more attention, and guidance. Some faculty members felt that if ‘this is just too hard then leave the program.’ At the same time, it was the University that invited me to meet their needs for federal compliance. The faculty, and administration needed to be educated on federal compliance laws. Unfortunately, the entire faculty did not support integration,” observes Dorsey.

Administrators, and faculty were openly resistant to black students obtaining a Ph.D. “It manifested itself in the types of assignments we received, how they were critiqued, and classroom remarks. It may not have been intentional, but you still felt the slight because of where you started in the race. My experiences at Bel Air, and then College Park as an undergrad did help me to adapt, and adjust. In a sense to become two people – a Black person in the Black community, and a white person in the white community. Dr. Huden was a light – I could go to him, and he was able to soften, and diffuse these inequities,” says Dorsey. Huden, his wife Gudrun, and their daughter, also welcomed Dorsey into their home, especially through the dissertation process. This is where they held their one-to-one meetings, and provided a safe space for Dorsey to write.

In 1999, Dorsey left his directorial role at UDC to work with the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food Agriculture. There, he worked as a national program leader to ensure the competitiveness of American agriculture through policy analysis, education, and support for state university operated economic ventures – all within the context of the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities (APLU). He was responsible for the administration of 9 million dollars of policy grants in the areas of trade, agriculture, food, and the environment. He frequently interacted with the faculty, and administration of the member institutions.

At USDA, all of the pieces of Dorsey’s career came together. It was the most nurturing environment he had ever been in. “Almost all of my colleagues were Ph.Ds, all of them had worked in land-grant universities, like Maryland, and I was dealing with an intellectual group of people, who were over the issues of homosexuality, and race. We could get down to business. We didn’t have a lot of baggage in our heads. We knew problems existed, and we factored those in, and we could focus on agricultural policies, diversity, urban programs, and other issues. All of the life experiences were a testing ground at USDA. Everything began to make sense, and just fit,” remembers Dorsey.

And as in the other critical points in his life, people stepped in, and took a personal, and professional interest in Dorsey. His sense of openness, and flexibility attracted mentors. “All of us have defining people in our lives. What you have to do is surround yourself with people who nurture, inspire, and urge you in a positive direction. I have had 20 amazing such individuals in my life,” says Dorsey. “I really wanted a happier life. Education was the key, and now I do live a very happy life,” he adds.

These days, Dorsey is an author. His first book, entitled Businessman First was published in 2014. It recounts the life of Baltimore’s first successful black entrepreneur, Henry G. Parks. Dorsey’s latest novel From Whence We Come, is based on his true story.

Having confronted discrimination, economic hardship, a resistant educational system, and self-doubt, the Maurice Dorsey of today openly shares this narrative with others. These days, he is able to reflect on his experiences with gratitude, candor, and wisdom. Says Dorsey, “I had some really tough days. Now, I feel comfortable with who I am. And given where I have come from, I consider my life a success.”

More information about Dr. Maurice W. Dorsey can be found here. This is the first of a three-part series with Dr. Dorsey within the Centennial Conversations: Diverse Voices in Graduate Education, in anticipation of the Graduate School’s 100th year in early 2019.

(Photo credit: Michael Gold)(Photo 2: June 1965)